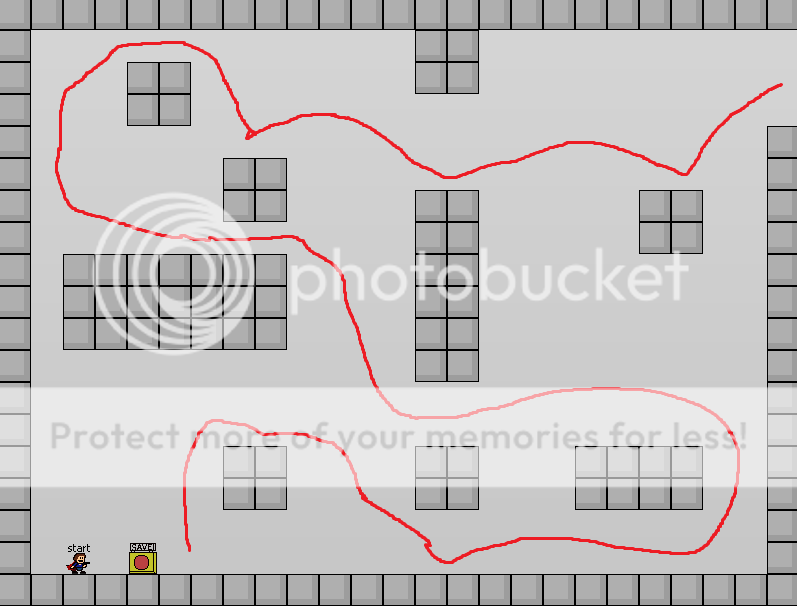

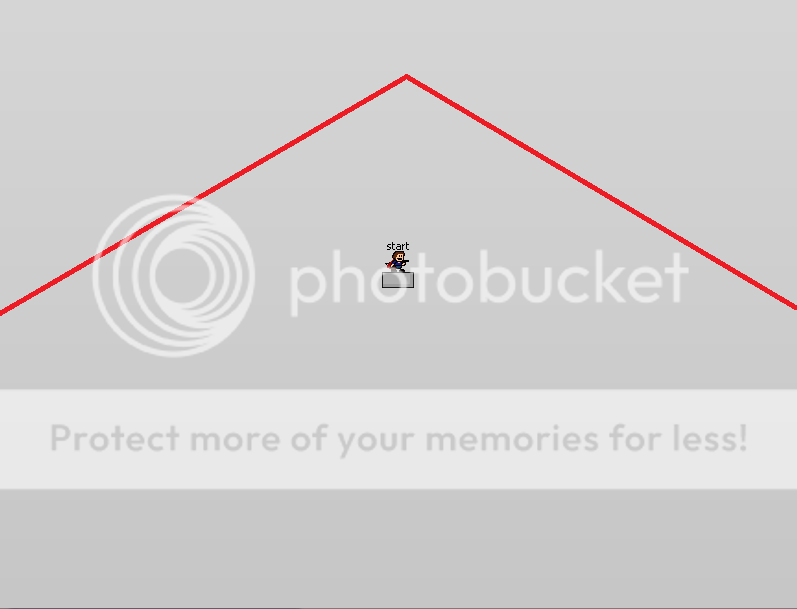

Basic Layout:

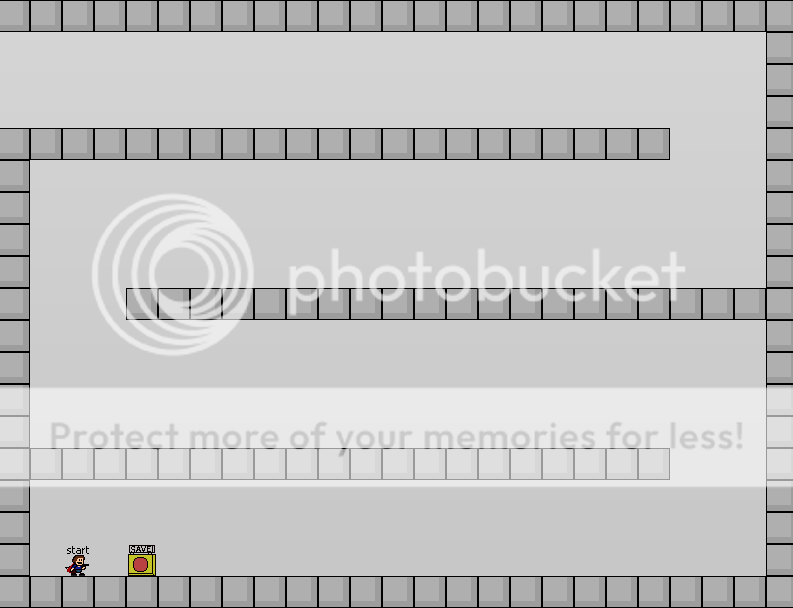

This is what a lot of people start with. It's a perfectly reasonable thing to start with, but it's also fairly intimidating. You have no idea where you want the player to go, what you want them to do on the way, or what obstacles they're going to need to get around in the process. Unfortunately, the natural response is just to make an exit and start working backwards to something like this:

In general, I try to avoid saying anything is outright bad. It stifles creativity to do so. The problem is that this layout stifles creativity too. Unless you plan on introducing some impressive mechanics, a game full of back and forth corridors like this just isn't going to be that interesting. Most of the times it just ends up being a bunch of generic jumps, like so:

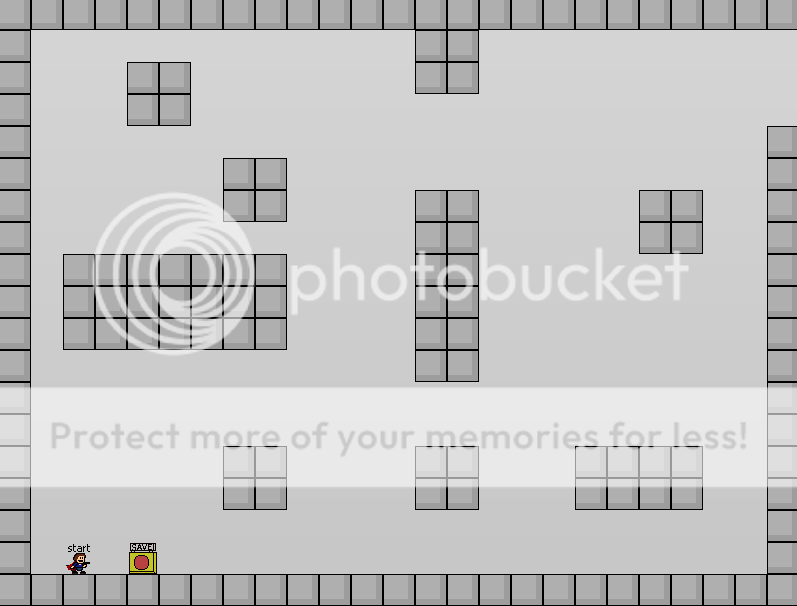

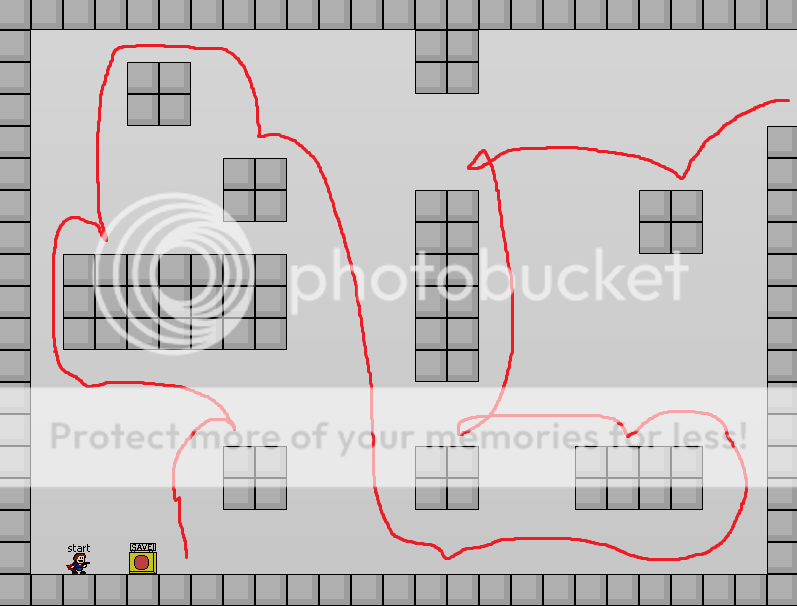

There's just not a whole lot to say about it frankly. You might be able to twist it into something that really shines once. Maybe you'll wring gold from the general layout two or three times even. You can get a lot more leniency from the player if you're willing to step a bit beyond your first inclination when it comes to room layout though, so let's try again. We start with the same empty room, but instead of a back and forth passage let's just throw some shapes in:

There's so much more that you can do right off the bat. You can have the same general back and forth if you want, but with a bit more variety:

You can have a much more vertical path than you could have before:

If you include triggers or other mechanics, the variety increases even more. To boil all that down: unless you already have a firm idea of what a room is going to look like when you start making it, beginning with just a few shapes scattered around a room can provide you with just enough possibility to be inspiring without being overwhelming.

A few guidelines that might help:

- Try to fill the room. Even if you take things out later, it's easier to make too much and remove some than too little and have the game feel empty (unless that's the point of course.) There are plenty of instances of people using less than the typical 800x600 pixel allotment without it hurting them, but think about why they're doing it if you plan on following suit. Graphical flourishes can also help fill space unused by platforming.

- Even if you avoid the usual back and forth hallway completely, be sure your replacement doesn't become as overused in your own game.

- Consider the direction of movement that we talked about before. Entering on the left side of the screen and leaving the right over and over is unnecessarily restricting even if the path there varies. Try entering from the top left and leaving from the middle bottom, or entering from the top right and leaving from the bottom right.

Jumps:

And so we reach the section that will probably annoy the most people. There are plenty of other places where you can see the formulations for the usual jumps, so I won't go into them here. I'm also not going to sit here and try to tell you to not use generic jumps. We all do it at some point or another. This is another opportunity to consider the spirit of your game. If you're comfortable putting six or seven gate jumps in a row and you genuinely think it's fun, you should feel free to do that. Just know that not everyone necessarily looks as favorably on that as you might.

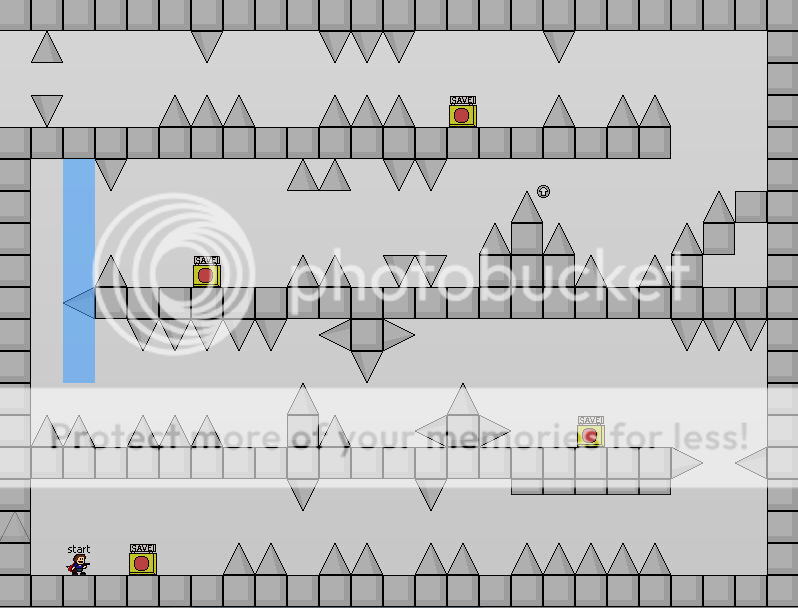

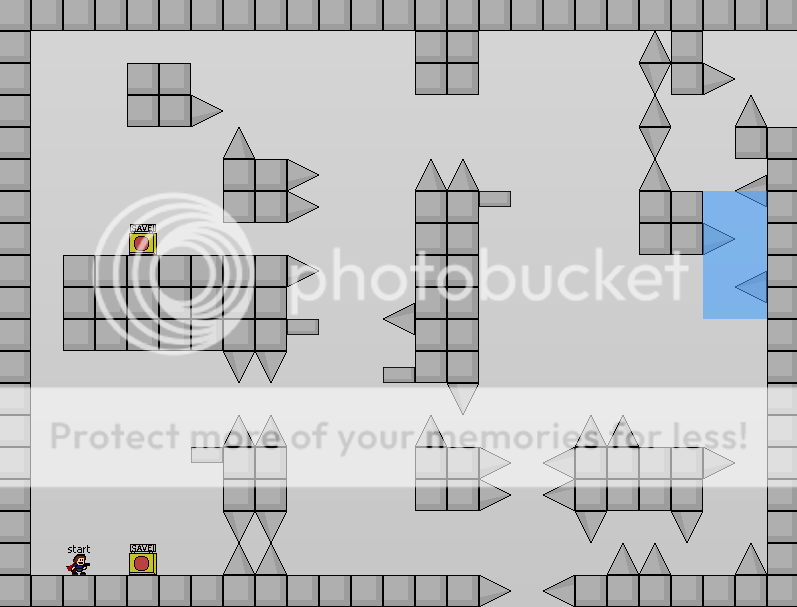

If you're less comfortable repeating the same jumps as everyone else but you're having trouble thinking of variety, let's refer back to that more interesting layout we were just using. Here's a version of it only using jumps I've seen hundreds of times:

There's nothing particularly wrong with this room (except for maybe the obvious skip.) Even with non-gray graphics I would argue it's pretty boring though. Three of the jumps are functionally the same, there's nothing super innovative about a diamond, and even the corners are oriented the same way. The problem is that watching hundreds of hours of these games has made certain jumps seem standard, or even necessary is certain places. Diagonals fit into their spots, as do diamonds, corners, etc. That's not to say that they have to go there, but rather that it can be hard to break out of the expectation that they

should go there. In the case that you feel like you're having this problem but don't want to introduce any mechanics quite yet, I would recommend changing the basic layout of the room some more.

I still wouldn't be entirely happy with this personally, but you can see how minor additions and removals to the landscape can drastically change where one is inclined to put spikes. I must admit I'm slightly biased here in the first place, but just remember that if you want to go with the old standbys there's absolutely nothing stopping you! I'm just looking to raise some alternatives to the standard.

Speaking alternatives, let's talk about jump refreshers!

Mechanics:

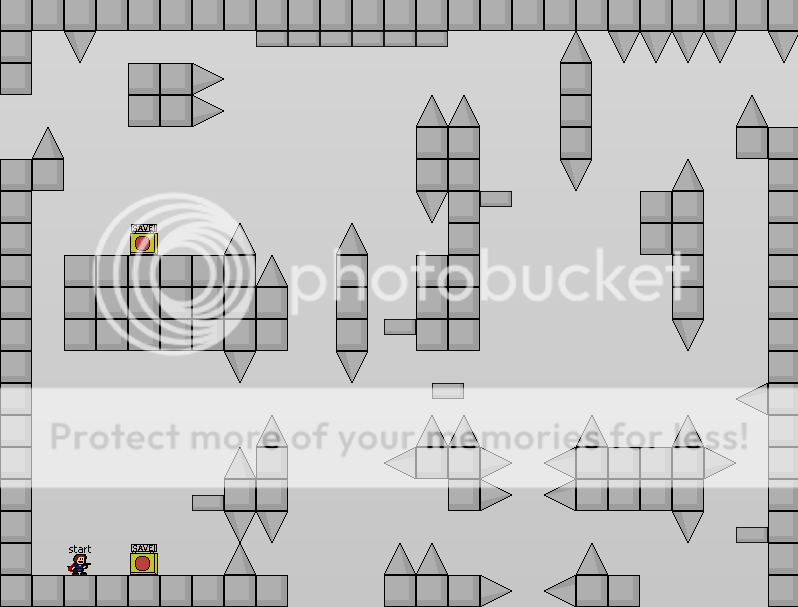

Not only jump refreshers of course, but everything that's additional to the usual platforming. I got into what mechanics were in a literal sense earlier, so now we're going to talk about them as possibility extenders. Here's a (not to scale) representation of everywhere the kid could conceivably reach in this room.

Everything above the red line is too far away, everything below it is not. If you add a jump refresher you would need to raise the red line though. Add a gravity flipper and you would have to invert it. Add water and there's no restriction at all. This is the intrinsic benefit of having additional mechanics in your game. Usually the player only has two jumps, but suddenly they have three! Or four! The rules that usually apply to what is possible and impossible suddenly no longer have any sway over you! If you ever reach a point where there's no feasible path for the player but you don't want to edit the room, there are always ways you can fix that!

Your ultimate goal with new mechanics should be designing the platforming around them instead of using them to repair faulty platforming, but in all fairness your first few games probably won't be your magnum opus anyway. There's no shame in experimenting even if it doesn't create the most elegant solution. A good rule of thumb for segments with mechanics is “if you can do it without the [jump refresher/gravity flip/water/etc,] you need to make the base segment more complex.”

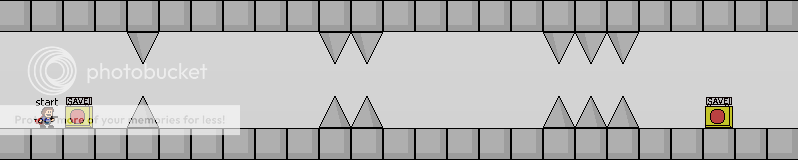

Game Flow:This time it's on a smaller scale, but let's talk about getting from point A to point B inside a room. Let's say point A is the first save and point B is the second. In most cases that's not a whole lot of platforming, but it's still important to consider how the player is going to be making that movement.

In this segment the player will be dealing with three individual points with their own difficulty. They will do an easy jump, then a tricky jump, then a hard jump. The worst you can say about it in terms of a difficulty curve is that the last jump is significantly harder than the first. The player has a sense of progression completing the three jumps despite that, going from something they can do fairly regularly to something that may take a while, and since it's a fairly short save there will be ample chances for them to get to the end.

A save like this will be called boring almost every time despite that. The first problem is that the player's direction is incredibly simple. It's a broken down segment of an already boring layout, and there's really no disguising it. The second problem is the repetition in the movements required of the player. To simplify a bit, the only thing required of them is holding right, jumping once, then jumping twice, then jumping twice again. Even if it's not the easiest thing in the world to execute, it's boring.

Most people expect a change in difficulty over time in a game, which means a change in difficulty between rooms, which usually ends up meaning a change between and inside of segments. Players expect to be forced to change what they're doing over the course of these segments no matter how the difficulty shifts. There's more than one directional arrow for a reason after all. Try varying the height at which they land, the length of each individual jump, and whatever other factors you can think of just to force the person playing to use the maximum range of movement possible to traverse the distance between saves.

Game Narrative:

And so we're back to this. I mentioned before that you want to decide on the atmosphere of your game before you start working on it. This is largely because creating an atmosphere is inevitable. Even if you have no music, an incredibly plain tileset, and just the most basic platforming, the atmosphere you have created is boring but not nonexistent. You may as well be the one directing it if one is going to exist at all.

Graphics are a bit hard to deal with since communicating visually in 32x32 tiles is a challenge, so let's just go right to music. You're probably going to have it in your game in some form! How should you pick it? It's not that hard really. Consider the important points on whatever kind of narrative chart you've constructed for yourself. Do you want the player to be getting excited as the boss nears or should they be dreading it? Should the new mechanic be filling them with energy or grinding them into dust? You can convey these sorts of things with music!

Unfortunately, I can't provide you with an easy chart or anything for that. Just listen to a wide variety of music, pick ones that convey the right emotions to you, and hope everyone else feels the same. Try running it by a few people! There will almost always be someone who gripes about the music anyway. An easy way to get an idea for it is to look at media embodying that particular emotion. Find a game filled with sorrow if you want to find some sad music, etc.

Going back to graphics for a moment, you can occasionally do the same depending on how resourceful you are. Find a game with a similar feel for the one you're going for and start there. Sometimes what's available can be surprising!

That's all!I realize that to some people, this doesn't answer your questions at all. If you're having a lot of trouble with the mechanics of design you can always try watching someone stream it or reading a book about it, and if you're having coding issues you can always ask here. What I tried to do was provide a framework for thinking about a game as an entire entity to give some direction to that creative process.

TL;DR: Where does the player start (in terms of location, emotion, and difficulty,) where do they end up, and what happens along the way? If you can answer these, you probably have a pretty good framework for a game.